If you’re into motivational books, you’ll probably recognize Paul Arden with his quirky book titles. I don’t usually read or buy motivational books – I tend to go for spiritual or religious ones instead. My favorite genres are history or philosophy, especially global knowledge. As for psychological books, most of the ones I’ve read were either gifts or ones I accidentally bought – you know, the cheap ones that look good but I had no idea what they were about or what the reviews said!

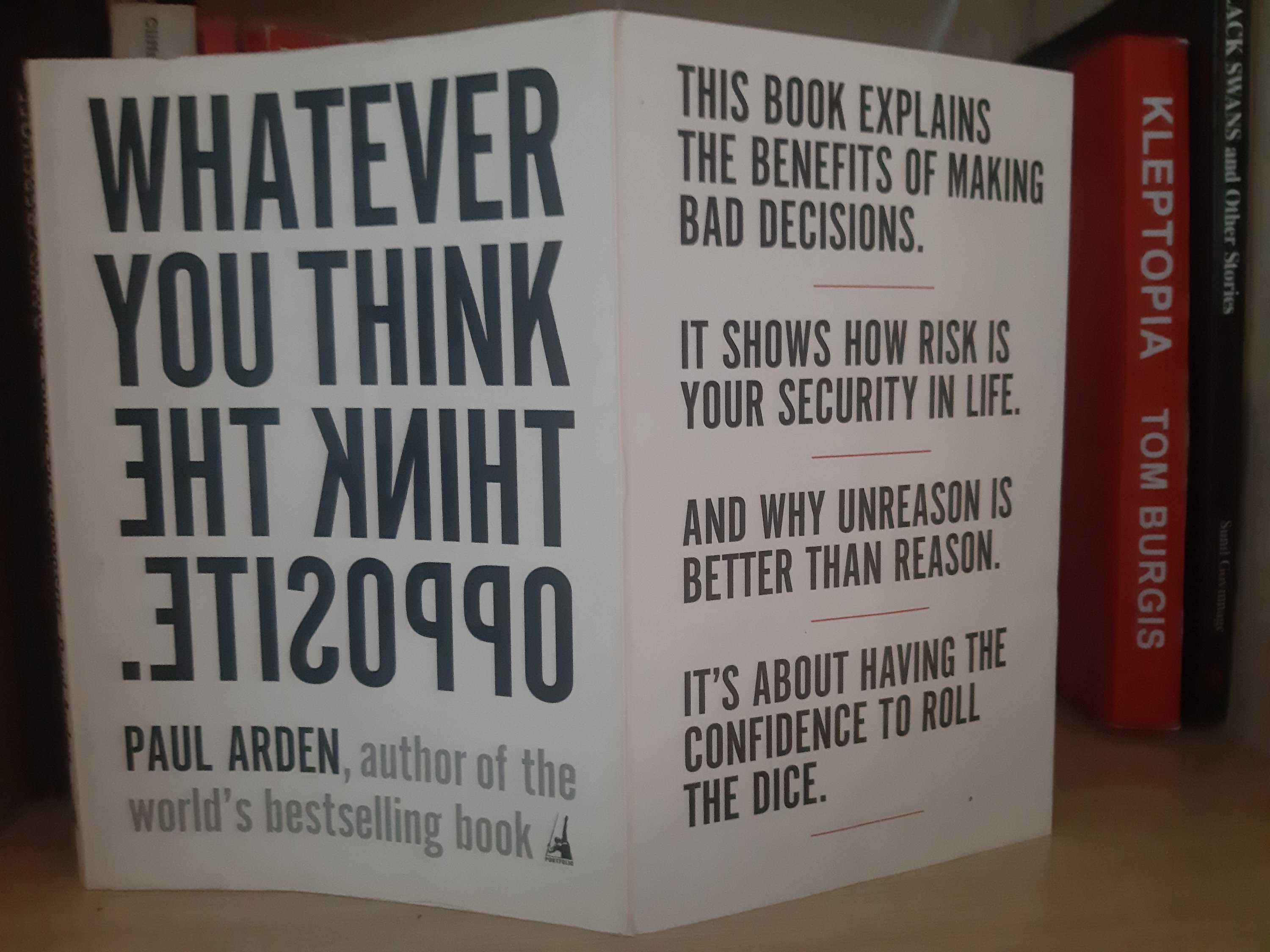

One of Paul Arden’s books was a farewell gift from two of my close friends at my old company. I thanked them happily and asked why they picked that book over others. I was curious if they thought it matched my decision to move on to another company. When I read the highlighted descriptions like “this book explains the benefits of making bad decisions” or “why un-reason is better than reason,” I was a bit surprised, wondering if they saw my decision that way. Turns out, they were just as surprised as I was! They had no idea the book had those descriptions – they chose it because it was one of the top books of the month at the bookstore.

Surprisingly, I enjoyed reading this Paul Arden book more than his other one, It’s Not How Good You Are But How Good You Want To Be (which was my friend’s). Through short, simple narratives, imaginative illustrations, and photography, Arden tried to challenge the paradox of what many people considered their achievements or failures. I thought it was a brilliant way to inspire readers to think deeply, but without making it boring. Unfortunately, not all of the ideas in these less than 150 pages were mind-blowing for me. Some felt a bit cliché, either because of the subjective narratives or the overused illustrations and photos – sadly, sometimes both.

For example, there was one page titled “Slap in The Face,” where Arden gave wise advice about how, if you wanted an objective opinion about your work or appearance, you should ask what wasn’t good instead of asking if it was good. I’m sure you’d agree that this advice was true, but to illustrate it, he used a photo of someone frowning after being slapped. I thought it was a bit too simple for such a meaningful idea, even though I understood that the expression in the photo showed pain. The part I liked the least was about resigning and being fired. Aside from the somewhat overbearing motivational advice, there was also no illustration for the full-page argument on either topic.

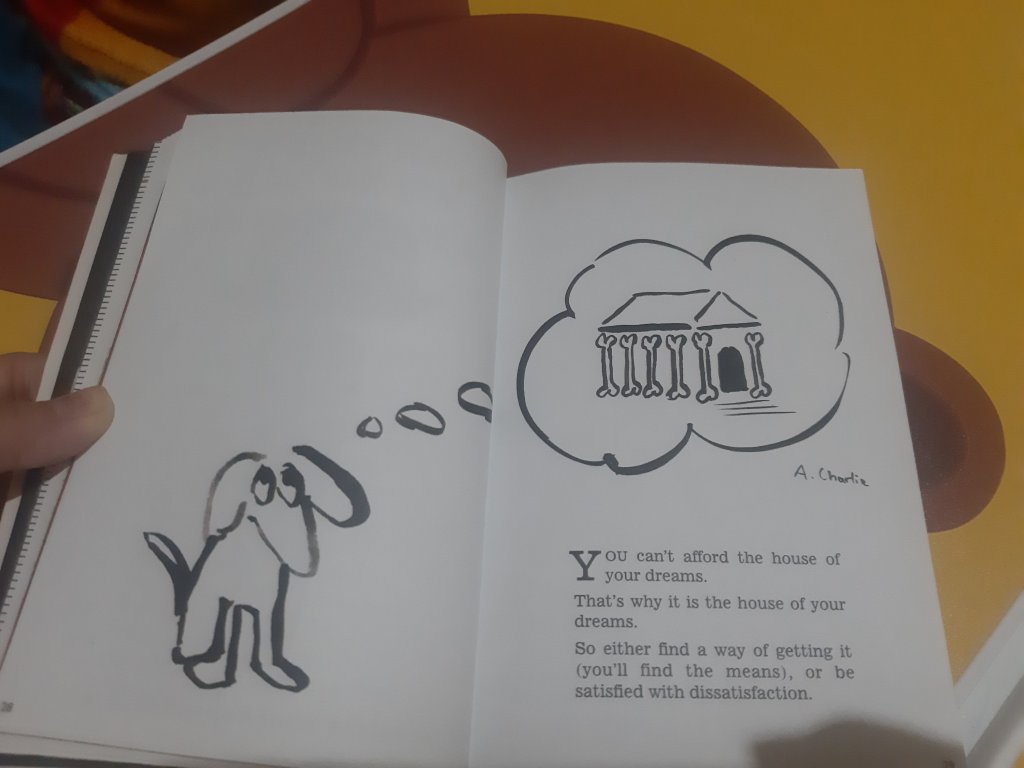

On another page, I wasn’t a fan of his idea that a dream house couldn’t be afforded, and that if someone had it, it meant it wasn’t really their dream house (pretty cliché, right?). But Arden kind of redeemed himself with the illustration he used: a black-and-white drawing of a dog imagining a house made of bones. At first, I thought the bones were the dog’s, meaning the house would only be built after the dog’s death. But then I considered that the bones could have been the dog’s favorite food or things, and the house would have been made out of the things the dog loved. That’s how the book let readers interpret things in their own way.

At this point, I realized that what was inside this book wasn’t just about motivation—or maybe it wasn’t about motivation at all. It was about creative thinking in psychology, something I only became aware of during my second read-through. I looked over the very first page, and it was written, “Let us start off on the right foot by making some wrong decisions” on a black background, with a small footnote illustration of a guy stepping forward with his right foot, accompanied by an arrow symbol. How did I not notice that the first time I finished the book?

While not all of the motivational philosophies in the book might resonate with everyone, it’s still a great read, especially with the quality and originality of the illustrations and photography. Arden listed the details of all the image creators on the last page, and I couldn’t help but wonder if he came up with the ideas based on existing works or if he asked the illustrators to create the drawings and pictures specifically for the book.

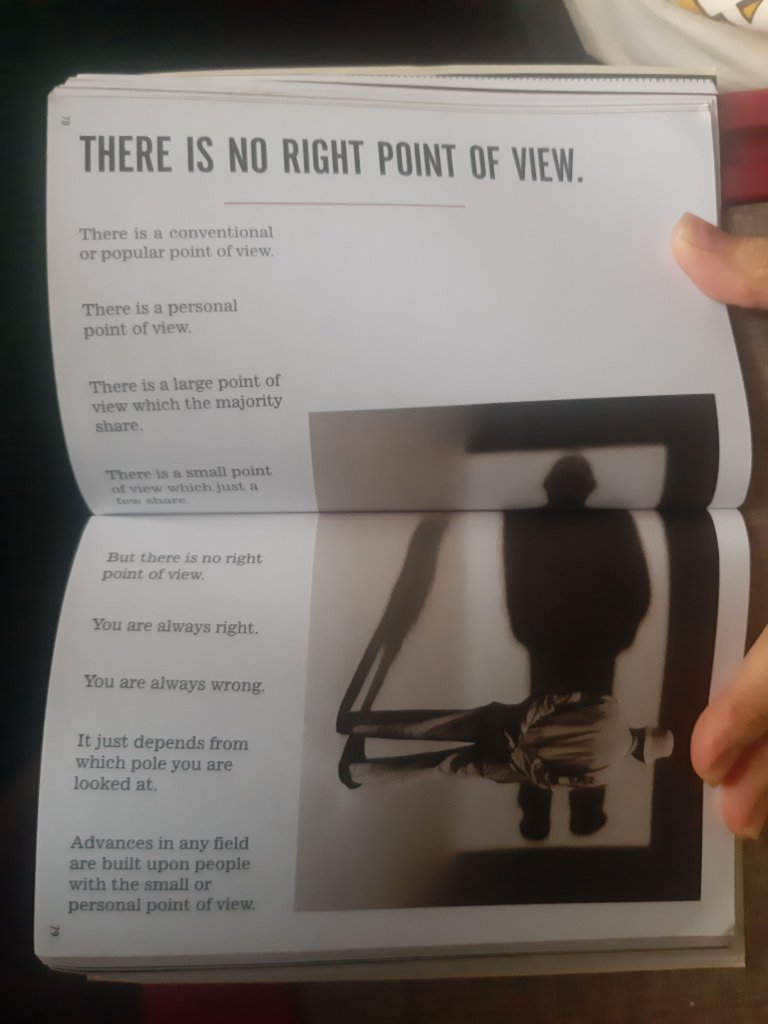

Two other things I recognized as the best philosophy and illustrations were in sections titled “There is No Right Point of View” and “Tips for Beginners.” I don’t need to explain further—you’ll understand why they were my favorites once you see the pictures I’ve included below.

As for Tips for Beginners, with its simple illustration of an empty cup and three biscuits, it became something I liked because it sarcastically relates to office politics—or maybe not just office politics, but pretty much anywhere.

Here are the three best keys to reading this book, in my opinion: be relaxed—don’t read it if you have a stressful mind, start reading without looking at any reviews, including this one, and pay attention to the illustrations—if you find the narration to be a bit off.

Oh, and if we had a book reading group, this would definitely be the type of book to explore and discuss. Everyone in the group would have different opinions on each chapter or illustration, which would really broaden our perspectives. Interesting, right? This reminds me of the historical drama novel and movie The Guernsey Literary and Potato Peel Pie Society. Despite its love and sad story, the book reading group in the isolated area of Guernsey Island during World War II was 100% inspiring for me. Another inspiring and funny reading group was Phoebe’s class in Friends—lol! The hilarious story of Rachel and Monica joining Phoebe’s class separately should ring a bell for Friends fans.