To combat the stress and sadness of what’s happening, and to lift our spirits from the monotony of staying at home, Desi Anwar’s mindful portfolio is truly worth reading—and re-reading. Last week marked my fourth time reading this (third time re-reading). I bought it and read it for the first time several weeks after its release in 2014.

Though this might have been her second published book, I believe it’s her first true written work for a book, as her first published one was a compilation of her phenomenal tweets. For those of us born in the 90s, like me, Desi Anwar has been a symbol of hope for the development of journalism in Indonesia. After reading this book, I realized I had mistakenly thought of her as a serious person who was always reading newspapers and discussing the news—lol. Ironically, every time I see this book, I think of one of my friends. Why? Because it was bought as a birthday present for her, but when I asked, “Have you read Desi Anwar’s book?” she responded by sending me a photo of the book’s Indonesian cover (yes, the red circle on the front is the English version, and the yellow one is the Indonesian version—I barely knew that at the time). So, I ended up with my own copy and gave her something else as a gift (and not a book, haha).

As simple as the title suggests, A Simple Life (Hidup Sederhana in the Indonesian version), is all about Desi’s perspective and experiences in learning to enjoy life’s simple pleasures. The book left quite an impression on me, and I highly recommend it, especially for those looking for inspiration or a spiritual boost, but who are tired of the typical motivational books full of life hacks. There are three key things I really appreciate about these 288 pages: the way the book is presented, the narration and diction used, and the chosen topics or chapters.

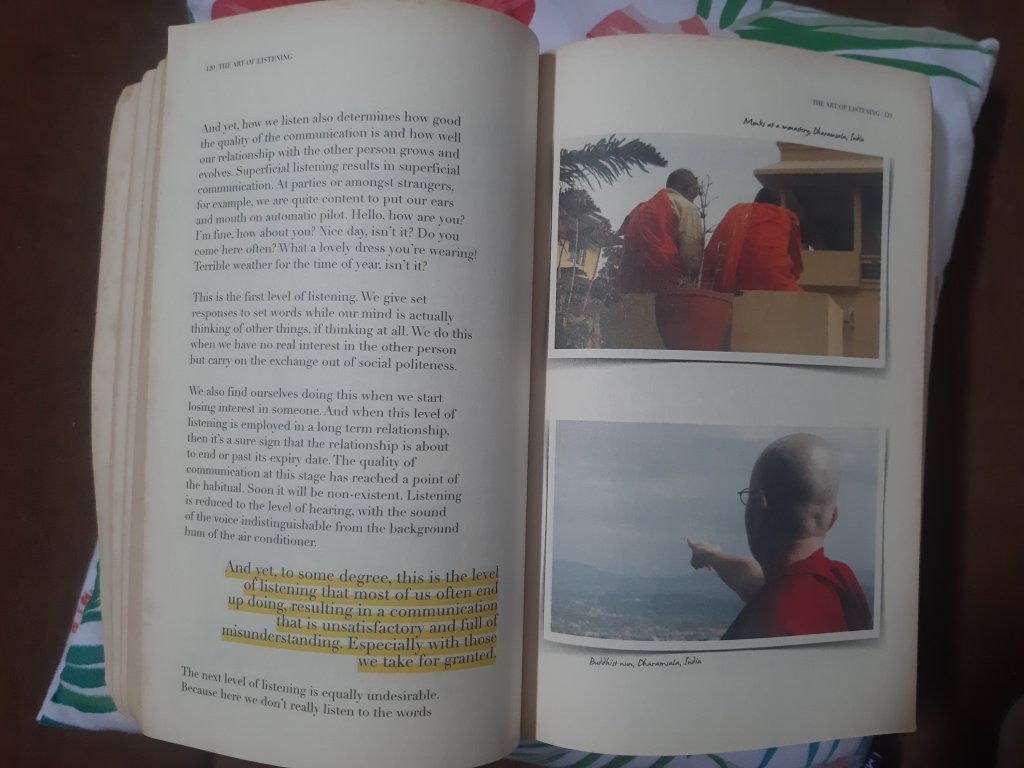

The book contains about 55 chapters, each one focusing on a specific topic, which is often a common aspect of life yet holds deep meaning. We can all agree that the topics are meaningful because Desi brilliantly explores their philosophy in a breathtaking way. Her narration is flawless, and her use of rich yet simple diction showcases her impressive literary and linguistic skills. I never encountered repeated ideas or narration. Each paragraph stands alone, with fresh perspectives, flowing naturally. Not to mention, she beautifully incorporated gorgeous photographs throughout the book, many of which were taken by her personally. Great literacy paired with stunning photography—it’s the perfect package for a journalist. A standing ovation for Desi Anwar!

This part may not be relevant to all readers, but in addition to being inspired and relaxed, I was also happy to learn more about Desi Anwar, especially since there aren’t many sources online that delve into her background. For example, who would have known that she had travel sickness since she was young? By reading this book, I realized that Desi, like other great people, was once an ordinary child who often wondered about others, had silly secrets and weaknesses, was influenced by those around her, but never stopped growing her mind. Once again, Desi didn’t share her success story in this book—not even a hint of it. Instead, she took us on a journey back to her childhood, describing her neighbors and friends. Growing up with her father, a professor in London, and living with her family, including her two sisters, most of her memories were about the people she met there.

Some parts of the story showed her deep admiration for her father. She called him a “lifetime learner,” and I could see how much influence he had on her. Like father, like daughter—her cool and tough character might have been inherited from him. In one chapter about illness, she mentioned her father’s memorable words when she fell ill with the flu (she didn’t mention her age at the time, but I imagine she might have been under 15, not yet a teenager): “Next time, try not to be sick. It’s very selfish. When you’re sick, you’re inconveniencing other people who end up having to look after you.” Wow! Her father’s words were surprisingly insightful. I agree that sickness is often the result of how we treat our bodies. However, as a mother now, learning about parenting, I would only say such words to my daughter if she repeatedly did things that made her ill. Well, we live in different times—some grandfathers might have even hit our parents or used physical punishment for not studying, right? Especially in Asian cultures, let’s just say Desi’s father was an advanced type of Asian parent 🙂

Of all the great chapters, one with the title Being Present stood out to me because the effort to truly be present is a challenge for every human, even someone as intelligent as Desi Anwar. She explained how people’s minds often wander, even when they are in a meeting or talking to us. She suggested that we train our minds to be mindful because it’s relaxing. She asked us to imagine truly enjoying every touch of our teeth as we brush them in the morning, instead of letting our minds wander. I totally agree. We teach children to focus their minds, but they struggle with it because they’re distracted by everything around them. As they grow, staying focused becomes their task again. As adults, we’re responsible for multitasking—doing this and thinking about that—which often leaves us with full minds but not necessarily mindful ones, affecting our thinking quality and productivity. If you’ve ever read books about the human brain, you’ll know that multitasking can be the enemy of our brain, even though it helps us complete daily tasks and career achievements. My religion also teaches us to be ‘khusyu’ (focused) during prayer, but many Muslims admit they often get distracted and start thinking about other things. I’m guilty of this too. If a prayer takes five to ten minutes, my mind will often wander, especially in the last two or five minutes, even though I hear no sounds around me. As Desi said, being present is a discipline of the mind. It’s not just for those working in creative industries, though many creators say their best ideas come to them while brushing their teeth, sitting on the toilet, or walking down the street. Most people would agree that a relaxed body and mind are much more conducive to brilliant ideas than a tired one.

In addition to my favorite parts in the chapters on Time and Busyness, a busy, productive person like Desi still confessed that, most of the time, many unnecessary things keep people busy. She mentioned distractions like gadgets, lingering over lunch or dinner, or extending unimportant arguments because of a bad mood. It’s true and relatable—many people spend extra time discussing simple problems. That extra time is often filled with unnecessary talk, entertainment, or waiting for members who are late due to prior unproductive meetings or activities. I remember one of my favorite lectures where the speaker said that many people who get angry or are in a bad mood because they’re stuck in traffic on the way to work often don’t have anything urgent to do once they arrive. About 20% of them may have to prepare for a scheduled meeting, but 80% of them might just procrastinate once they get to the office.

Desi’s perspective in all the chapters is subjectively objective, meaning readers might get inspired, even if they agree with some parts and disagree with others. For instance, I had a different opinion when she used her art teacher as an example of time management—how she still managed to make homemade jam and swim before going to work. The example wasn’t critically wrong, but I believe Desi could have chosen a role model with a more complicated set of responsibilities or activities than an art teacher. Also, in the chapter Watching What We Eat, while the story and theory aren’t biased, it might come off as too serious or boring for some readers. She shared the story of a friend who used to smoke and eat heavy carbohydrate foods. Personally, I can relate to this. I joined an NGO community focused on Indonesia’s food security, and for several years, I tried to consume fewer imported products, fruits, and any foods made from imported raw materials. We believed we were doing it because we cared about society, regardless of what others thought.

I, too, have found myself in a situation where I judged someone else’s eating habits. Several years ago, I went on a dinner date, during which my companion remarked that the food I ordered might not be beneficial for my health, based on the combination of ingredients. While I don’t recall the precise details, we were dining at a Greek restaurant, and I had selected two dishes: one featuring salmon and the other incorporating Greek yogurt. He suggested that the high protein content in the salmon, when paired with the probiotics in the yogurt, might overwhelm the body. My initial instinct was to question, “Do you always analyze food this way? Why?” or something even more brusque, such as, “Please, let me enjoy these delicious dishes!” However, I refrained from voicing such reactions and instead chose to engage in a more rational dialogue, posing questions such as, “Is this claim scientifically substantiated?” “Do you truly believe this combination is problematic, given the modest 100-gram portion?” and, “What specific impact would this have on the body?”

Influencing others is never easy, especially when criticizing their habits or beliefs. But Desi, through this book, has managed to influence many readers in a relaxed, non-judgmental way, without offending anyone. I won’t share any more details here because this book should be experienced firsthand. You should read it—or at least look at the photographs and highlighted quotes.

Happy weekend! Stay healthy and stay sane!